5 interesting learnings from Revenue per Engineer data at 300+ companies

Top-performing companies see $1.5M+ Revenue per Engineer.

Welcome to the latest issue of Engineering Enablement, a weekly newsletter sharing research and perspectives on developer productivity.

The DX Core 4 combines DORA, SPACE, and DevEx into a single framework, providing a paved road for measuring developer productivity.

One of the metrics included in the Core 4, Revenue per Engineer (RpE), has been a recent focus area of our research. We just wrapped up a study that I’ll cover later in this article. But first, some personal backstory around RpE…

The first time I heard someone suggest RpE as a developer productivity metric was at a leadership meeting at GitHub. We were having a spirited debate about how developer productivity should be measured, and Nat Friedman, then-CEO of GitHub, suggested revenue per engineer.

At the time, I thought this was a weird suggestion (more on this here). But the more time I spent working on developer productivity, the more the idea grew on me. After all, increasing developer productivity is about gaining leverage and driving higher ROI per developer. So what better way to measure this than by revenue?

Revenue per engineer is measured by dividing your company’s gross revenue by the number of full-time employees in R&D. Longitudinally, RpE can provide really interesting trends and insights. When compared against similar companies, RpE provides a great snapshot of how your org compares.

RpE is also a great way to frame and articulate the value of engineering productivity investments. I often hear business executives describe their engineering function in terms of “how efficiently the organization can convert input (i.e., salaries) into revenue for the business.” RpE captures this idea perfectly.

Since January, our team has been working on collecting benchmark data for Revenue per Engineer. You can go here to get the full report, or continue reading to check out some of the highlights. We collected data in collaboration with VC and growth investment firms including ICONIQ Growth and Brighton Park Capital. Our dataset consists primarily of SaaS companies, but the findings are relevant industry-wide.

Here are some of our key findings.

1. Top-performing companies see $1.5M+ RpE

The median company sees an RpE of $892K, with top-quartile companies reaching $1.5M+. The table below shows the benchmarks by revenue range—use these numbers to get a sense of where you stand.

Interestingly, while RpE tends to increase with company revenue, the gains level off after $500M. This suggests there’s a baseline level of efficiency most companies hit and then maintain.

Of course, there are notable outliers that show what’s possible. Among public companies, Netflix, Spotify, and Toast stand out—Netflix with an RpE of over $10M, and Spotify and Toast exceeding $5M.

2. Fast-growing companies trade efficiency for growth

As we analyzed our data, we wanted to see if year-over-year revenue growth affects engineering efficiency. Our hypothesis was that faster-growing companies have lower RpE—and that’s exactly what we saw.

The faster a company grows, the lower its RpE tends to be. This is likely a result of companies hiring aggressively in R&D to drive growth before those investments start bringing in revenue. In other words, lower RpE during rapid growth isn’t a bad thing.

This underscores an important point about Revenue per Engineer: it’s a better signal for mature organizations. It shouldn't be the primary focus for fast-growing companies.

This report didn’t look at whether companies using AI are more efficient. Right now, AI adoption is all over the place, and the impact is mixed. But here’s our hypothesis: as companies get smarter about how they use AI—rolling it out in a structured way and educating developers on the best use cases—we’ll start to see a new trend emerge: organizations that are both growing fast and operating efficiently.

3. Larger engineering organizations show lower RpE

When we looked at how Revenue per Engineer changes with engineering team size, we found something interesting: both the smallest and largest engineering organizations tend to have the lowest RpE.

Small teams (<50 engineers) show the lowest RpE overall, but the data is highly variable. Some have RpE as high as $3–6M per engineer, while others fall below $500K. These teams are less predictable and more sensitive to early-stage dynamics.

Large orgs (1,500+ engineers) also show lower RpE, which was unexpected. Companies generating the most revenue had the highest RpE figures, however our data shows a different pattern when it comes to team size. Efficiency increases as engineering teams grow—until they pass 500 engineers. After that, it starts to decline and eventually levels off.

4. Outsourcing to vendors increases RpE

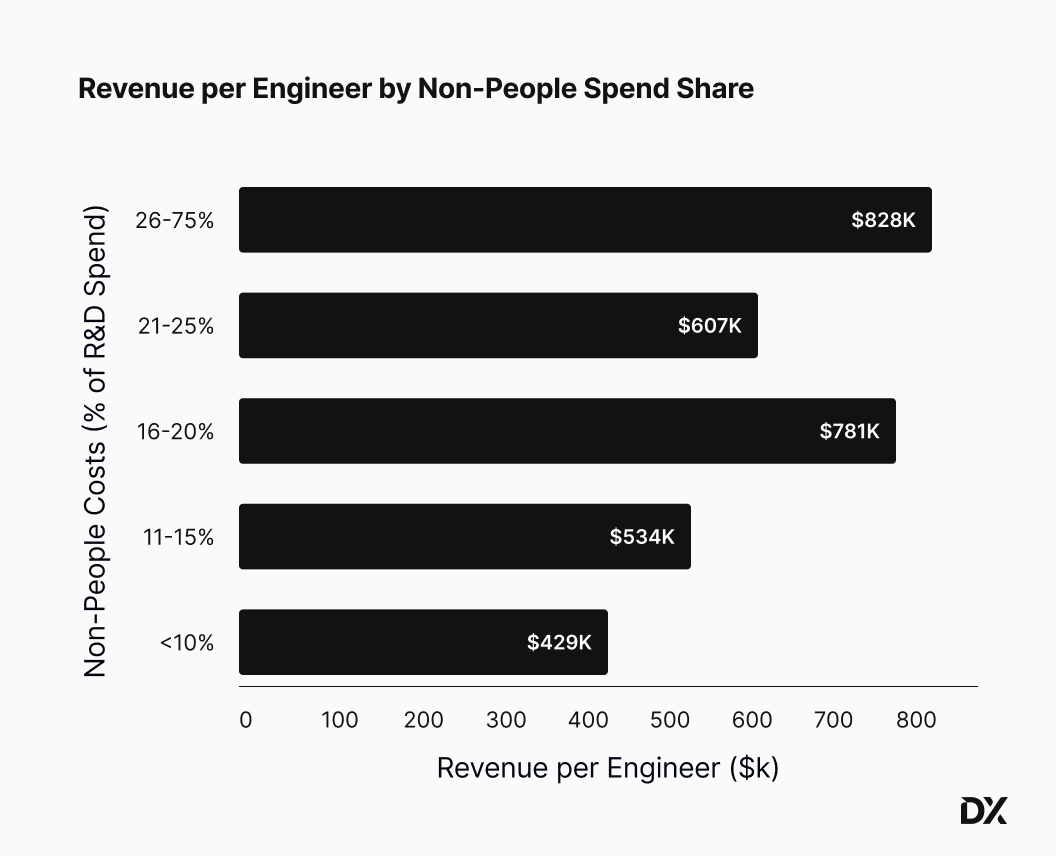

Some companies are known for primarily building in-house, and we were interested to see if these companies are more or less efficient long term. We looked at how companies allocate their R&D spend across three categories: people costs, contractor costs, and non-people costs (i.e., vendor tools and services).

Companies that allocate a higher percentage of their total R&D spend towards vendor tools and services show higher Revenue per Engineer. This suggests that investing in automation and tooling may allow engineers to spend less time on repetitive work and more time on higher-value work that drives revenue.

5. Recently founded companies are more efficient

We also observed in our data that companies founded after 2010 are 27% more efficient than those founded earlier.

While it’s intuitive that newer companies are more efficient, the size of the gap was surprising. This suggests that newer organizations are benefiting from building atop modern tech stacks, leveraging modern go-to-market strategies, and having digital-first business models.

Another factor that may be contributing to this disparity is the impact of acquisitions. When a company acquires another organization's tech stack, it immediately introduces layers of complexity to their overall architecture, which may translate to a lower RpE.

Final thoughts

Revenue per Engineer doesn’t tell the whole story—it’s a lagging metric, and one that doesn’t capture the full complexity of engineering work. But when benchmarked and paired with other metrics, like those in the DX Core 4 framework, it becomes a helpful lens for understanding engineering efficiency.

For executives, RpE provides an actionable reference point to track and discuss. For Developer Productivity leaders, it contextualizes investments in tools and processes within broader organizational objectives.

Leaders can predictably improve RpE by systematically removing friction and waste getting in their team’s way. Companies like Block have done exactly that—they used data to identify the biggest opportunities, which, for them, were to invest in IDEs, golden paths, and AI.

Go here to read the full report.

Who’s hiring right now

This week’s featured DevProd job openings. See more open roles here.

Snowflake is hiring a Director of Engineering - Test Framework | Bellevue and Menlo Park

Adyen is hiring a Team Lead in Platform Engineering | Amsterdam, Netherlands

Scribd is hiring a Senior Manager - Developer Tooling | Remote (US, Canada)

UKG is hiring a Director and Sr Director of Technical Program Management | Multiple locations

Lyft is hiring an Engineering Manager - DevEx | Toronto, Canada

That’s it for this week. Share this issue with someone you know who might find it interesting:

-Abi

This metric is very similar to R&D investment as % of revenue, which is often used to define an engineering organization budget. R&D budget is framed via financial terms rather than headcount, but otherwise it's proportional to RpE.

So, in some ways, this metric is measuring something that's already baked into the budget. If revenue goes down, then the budget and headcount will be reduced too. The metric will remain as-is: it won't reflect engineering efficiency.