The AI Divide

MIT NANDA’s 2025 report on what separates successful AI pilots from those that stall, and how the role of engineers is evolving.

Welcome to the latest issue of Engineering Enablement, a weekly newsletter sharing research and perspectives on developer productivity.

🗓️ We recently announced DX Annual, our flagship conference for developer productivity leaders navigating the AI era. Go here to learn about the event and request an invite to attend.

This week, I’m summarizing “The GenAI Divide: State of AI in Business in 2025,” a report that MIT’s Project NANDA (Networked Agents and Decentralized AI) produced earlier this year. The report examines why, despite massive investment in AI, most organizations are seeing little to no business impact. Drawing on interviews, surveys, and analysis of hundreds of AI initiatives, the authors argue that enterprise AI outcomes have split into two camps: a small minority extracting real value, and the rest stuck in pilots. They call this gap the GenAI Divide.

For DevProd and Platform leaders, this report provides a useful lens for understanding why AI initiatives stall inside engineering organizations. It also counters the “AI will replace engineers” narrative.

My summary of the paper

Headlines often suggest that engineers will soon be replaced by AI, or that the software industry is on the brink of collapse. While AI tools are improving quickly and demos are impressive, Project NANDA set out to study how organizations are actually using these systems in practice. As the authors put it, the GenAI Divide reflects “high adoption but low transformation,” with 95% of organizations seeing zero measurable return.

The researchers conducted 53 structured interviews and collected survey responses from 153 senior leaders. The observation window covered roughly six months following initial AI pilots, and the authors are careful to describe the findings as a directionally accurate snapshot rather than a definitive market analysis.

Here are the key findings from the report.

The pilot-to-production gap

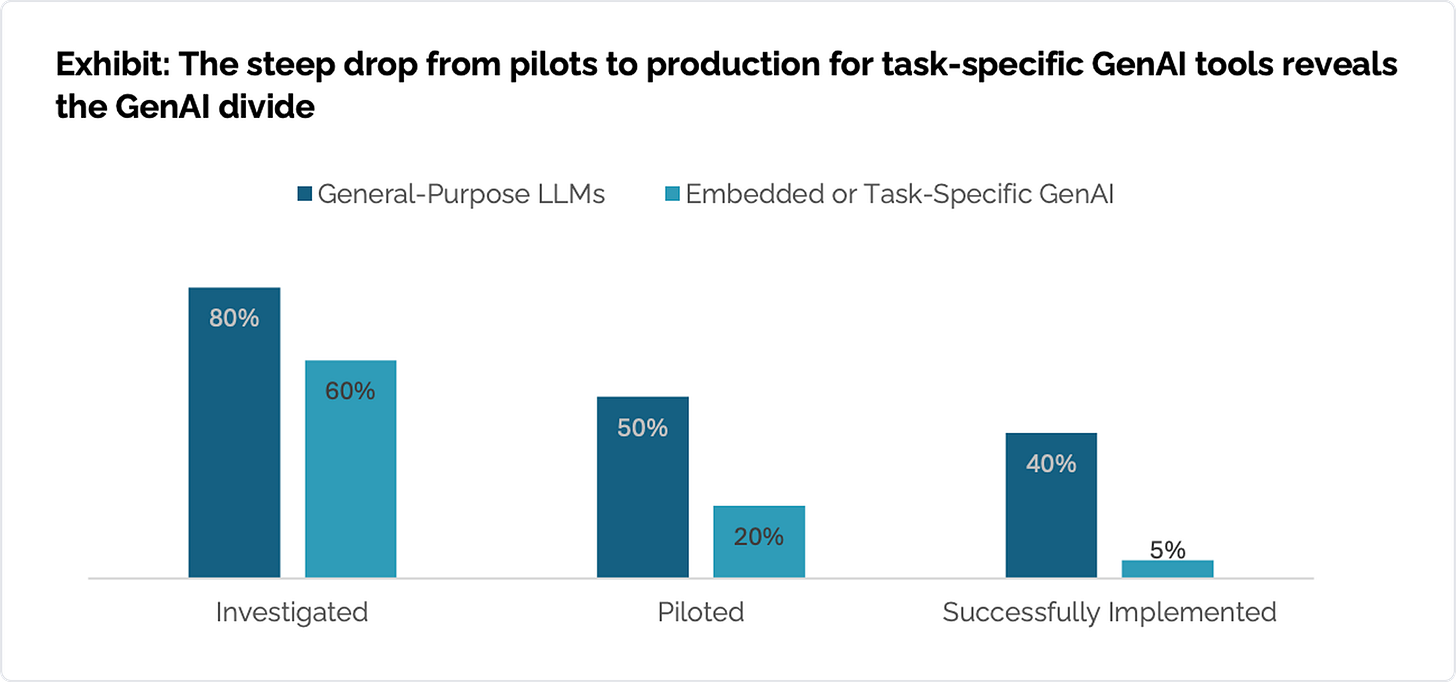

The most visible expression of the AI Divide is the steep drop-off from experimentation to real deployment. While many organizations evaluate AI tools, very few succeed in moving them into production. Roughly 60% evaluated task-specific or enterprise AI systems, about 20% reached pilot stage, and just 5% deployed systems that delivered sustained productivity or P&L impact.

Large enterprises struggled most with this transition. They led in pilot volume and investment, but had the lowest rates of successful scale-up. Mid-market organizations moved faster and more decisively, often reaching full implementation within 90 days. Across successful cases, the difference was ultimately about focus:

Successful teams focused on narrow, workflow-specific use cases with clearly defined operational outcomes, rather than broad or generalized AI deployments.

Implementation ownership sat with domain leaders and frontline managers, not centralized AI labs or exploratory teams, enabling faster decision-making and clearer accountability.

AI systems were embedded directly into existing tools, processes, and data flows, reducing context switching and allowing them to operate within day-to-day work rather than alongside it.

Buy beats build

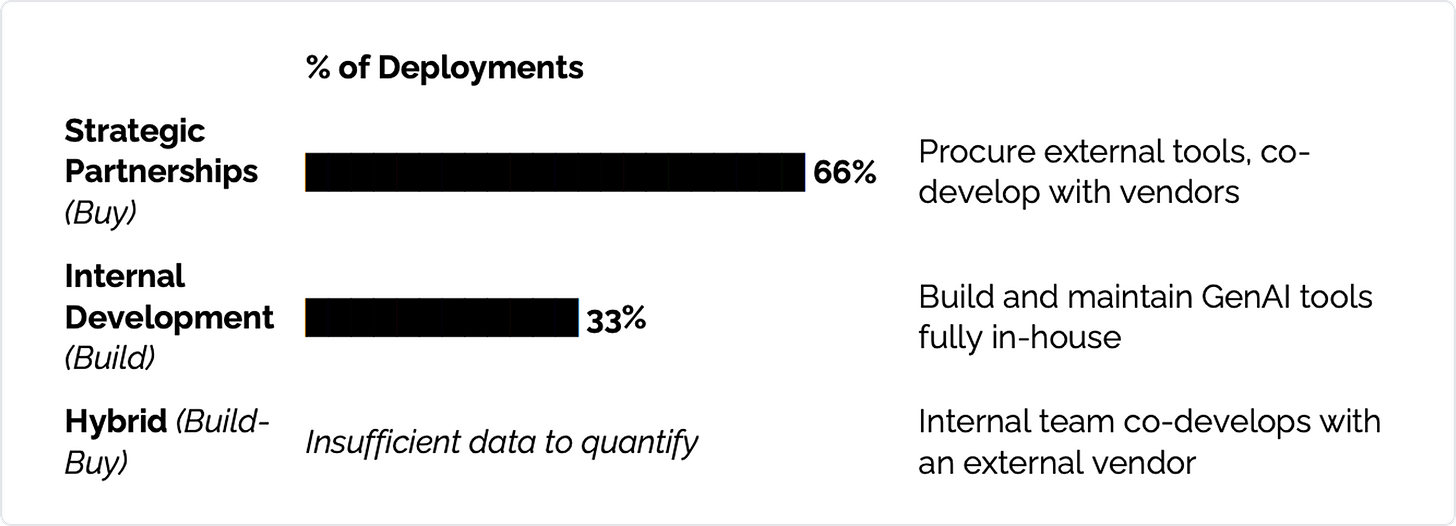

Organizations that crossed the AI Divide approached implementation differently. Rather than building AI systems entirely in-house, they were far more likely to partner with external vendors. Externally sourced tools reached deployment at roughly twice the rate of internal builds, which frequently failed due to brittleness and poor workflow fit.

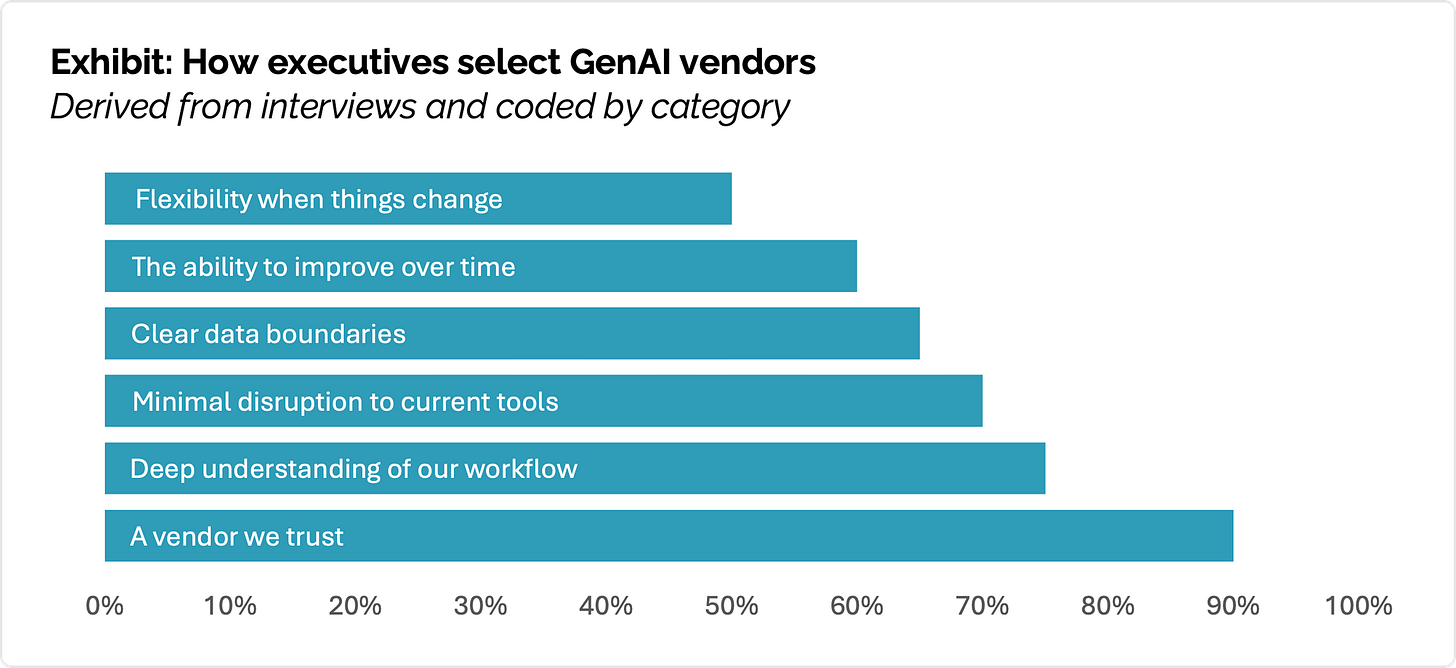

Additionally, successful buyers treated AI vendors less like SaaS providers and more like service partners. They demanded deep customization, evaluated tools based on measurable outcomes, and expected systems to integrate into existing workflows with minimal disruption.

Individual productivity gains are not the same as organizational transformation

The report makes it clear that while many teams report that AI helps engineers move faster on specific tasks, those gains rarely translate into systemic impact unless teams design the workflows around them. Two critical reasons highlight this point:

70% of users in the study prefer AI for quick tasks like generating simple unit tests or performing basic refactoring, but for complex projects involving multi-week work and stakeholder management, 90% of users still prefer human colleagues.

66% of executives noted that they want systems in their core workflows that learn from feedback and have more robust memory, while many agents repeat mistakes and fail at complex tasks repeatedly.

As one CIO interviewed noted: “Once we’ve invested time in training a system to understand our workflows, the switching costs become prohibitive.” For now, AI will remain a powerful feature of the engineer’s overall toolkit, but not a replacement for the engineer.

Ultimately, the dividing line between human and agent isn’t just “intelligence,” it’s context. Engineers don’t just generate code; they maintain a mental model of the codebase, the business requirements, and the team’s historical preferences, culture, and style. Current AI solutions lack the contextual adaptability and true persistent memory necessary to perform complex human tasks.

Humans remain in the loop

Across the successful deployments examined, a consistent pattern emerged: AI systems were designed to augment human judgment, not replace it. Engineers remained responsible for architecture, correctness, and evolution, while AI handled acceleration, suggestion, and pattern recognition within defined constraints.

Analyzing the findings shows that the future isn’t one in which engineers disappear, but rather one in which their roles shift. There’s less time spent on toilsome rote work and more on the difficult problems of system design, quality, integration, and decision-making.

Final thoughts

The most revealing takeaway from this report is where AI adoption breaks down. The sharp drop from pilots to production suggests that real constraints only surface once AI is embedded in long-lived, complex workflows. That same pattern makes claims about AI replacing engineers feel premature.

If AI were truly ready to replace engineers, we would already be seeing faster delivery at scale, shrinking teams, and systems that reliably design, build, and integrate software with minimal human oversight. Instead, the report shows that most AI efforts fail at the point where real-world context, dependencies, and coordination matter most.

This represents more responsibility for engineers, not less. Software engineering has never been just about producing code. The companies getting real value from AI aren’t the ones trying to eliminate engineers. They’re the ones who understand AI’s capabilities to significantly increase throughput and innovative capacity. These teams invest in adoption, integration, and measurement.

This is the final issue of the Engineering Enablement newsletter in 2025. Enjoy the holidays, and we’ll see you in January.

Fantastic summary of NANDA's work. The pilot-to-production gap really nails the core issue, we're seeing exactly this patern where teams get excited about demos but then hit a wall when they try to integrate into actual workflows. The observation that successful orgs treat AI vendors as service partners rather than SaaS providers is underrated, that shift in mindset seems to be one of the key unlocks for getting past the 5% threshold.